Hitting the ball hard is very important in the modern game of baseball. It is no coincidence that almost all of the big contracts go to sluggers, while soft-hitting contact hitters have an increasingly hard time making it in today’s game.

There are many reasons for this. For one, sabermetrics have shown the value of slugging, even if the traditional batting line doesn’t look impressive. Additionally, pitchers have such nasty stuff that stringing together hits is difficult, so getting the big hit before your third out is crucial.

To analyze this type of hitter, I looked at aggregate data from 2017 to 2024, limiting my sample to hitters with at least 1,000 plate appearances. I further specified my criteria to hitters who never exceeded a maximum exit velocity (max EV) of 109 mph. I chose 109 because max EV is closely correlated with the ability to generate power. However, occasional outlier spikes occur, and setting a lower threshold would have resulted in too small a sample size. For example, Luis Arraez hit 108 mph once, but in other years, he was between 103 and 107 mph. As a result, most hitters in my dataset typically fall within the 105-107 mph range.

Performance of Low Max EV Hitters

Overall, this group of hitters did not perform well. I analyzed a CSV with python and got the following data for that group.

Figure 1: Statline of low max EV hitters

This group had an 85 wRC+, a .252 BA, a .318 OBP, and a .369 SLG with a .117 ISO. The latter two numbers are distinctly below average. Clearly, being a soft hitter puts you at a significant disadvantage. From 2017 to 2024, 486 different hitters recorded at least 1,000 plate appearances. Of those, only 51 hitters (10.5%) had a max EV of 109 mph or lower and reached 1,000 PAs. This means it is already difficult to accumulate meaningful playing time with this profile.

However, it gets even tougher: only 19% of those hitters—just 10 overall—achieved a wRC+ of 100 or higher.

Figure 2: Leaderboard of low max EV hitters sorted by wRC+

By comparison, 52% of all hitters with at least 1,000 PAs had a wRC+ of 100 or higher. What makes this number even more striking is that the low EV group is already pre-selected, as very few soft hitters even reach 1,000 PAs. This means that the ones who do must possess special skills.

Some of this is due to defense, but even on the hitting side, this group has some specific traits. The low EV group (Figure 4) has a lower chase rate (.271) than the overall group (Figure 3) at .281, a higher contact rate (.825 vs. .772), and a lower K rate (18% vs. 21.9%). Despite these advantages, they still performed significantly worse overall (86 wRC+ vs. 101 wRC+).

Figure 3: Overall group of hitters with 1000 PAs between 2017 and 2024

http://” alt=”https://i.postimg.cc/6qWR8h5P/IMG-4.png”

Figure 4: Low max EV group

What Makes the Best Low Max EV Hitters Successful?

Now that we’ve established that having a low max EV is a major disadvantage (which is no surprise), the more interesting question is: what makes the successful low EV hitters good? To explore this, I analyzed the aggregate statistics of the 15 best and 15 worst soft hitters.

Figure 5: Average stats of 15 lowest wRC+ hitters

Figure 6: Average stats of 15 highest wRC+ hitters

From these figures, we see that the better-hitting group has a lower K rate (15% vs. 21%). Their barrel rate is slightly higher, but not by much. Surprisingly, there is no significant difference in walk and chase rates. This doesn’t mean chase rate isn’t important, but it seems to be more of a prerequisite for reaching 1,000 PAs rather than a defining factor for success. Launch angle numbers are similar between both groups, but the better group has a slightly higher pull rate, which may contribute to their marginally better power numbers of the stronger group (16 HR overall vs. 12 in the weaker group).

Figure 7: Corelation of stats with wRC+

also examined the correlation of different stats with wRC+ (Figure 7). Apart from the slash line stats, K%, IFFB%, and hard-hit rate had the highest correlation with wRC+, while launch angle and spray profile had relatively low correlations. The lowest correlation was found in patience metrics, confirming what we saw earlier.

Traits of a Successful Soft-Hitting Prospect

Based on this analysis, here are the key traits I would look for in a young, soft-hitting prospect:

1. K rate below 16%

o Only 7 out of the top 20 wRC+ hitters had a K rate above 16%.

2. Infield Fly Ball (IFFB) rate below 8%

o 12 out of the top 20 wRC+ hitters were below 8%. Only 4 were above 10%.

3. ISO above .100

o Only 2 out of the top 20 hitters had an ISO below .100.

4. Above-average plate discipline

o This doesn’t necessarily guarantee success, as both the top and bottom groups had similar patience metrics. However, it appears to be a necessary trait for earning meaningful playing time. Only 4 out of the top 20 had a chase rate above 30%. While good plate discipline won’t guarantee better than an 85 wRC+, it may help prevent falling to a 60 wRC+ level (i.e., a Quad-A player).

Other traits, such as a good barrel rate and a balanced batted ball profile, obviously help, but among hitters with little power, they don’t seem to be the highest priority. What stands out is that most successful soft hitters have fairly average batted ball profiles—not extreme fly-ball and pull tendencies, nor extreme opposite-field ground-ball profiles.

A low-power hitter who doesn’t project to hit more than 8-12 homers has no margin for weaknesses. They must do all the “little” things well to add up to something decent. Plus contact ability is essential. A slightly above-average contact rate (18-20% K rate) is often not enough. Ideally, K rates should be below 15-16%, which likely translates to 12-13% in the minors.

Some sneaky pull-side lifting power is valuable, turning a 9-HR hitter into a 14-HR hitter. However, this must not come at the cost of too many pop-ups and weak fly balls, which could drive BABIP down to .270 and tank value by dragging down batting average.

Above-average plate discipline helps mitigate weak contact and swing-and-miss issues, but even the most disciplined 40-grade power hitters likely won’t post elite walk rates. Many of these hitters walk 12% in the minors but drop to around 8% in the majors because pitchers will challenge them more. This means a significant portion of their value relies on batting average, making both strikeouts and low BABIP critical concerns.

The latter will make it tough because hitting the ball softly will negatively affect BABIP. Thus, players who post high BABIPs despite low power will need an exceptional ability to avoid pop-ups and extremely weak grounders (i.e., having a high sweet spot percentage on Statcast). Luis Arraez is a good example. He actually chases quite a lot compared to others in the group, which seems to be an intentional decision, as he wasn’t doing that earlier in his career. While not ideal, he makes it work by being top 10 in the league in pop-up rate and sweet spot percentage.

Generally, this makes some of the soft-hitting, high-performing minor league hitters hard to project because the minors can boost their stats—leading to fewer strikeouts and, in some cases, enhanced power, particularly in PCL parks. Additionally, MLB defenses are better and more tailored to specific hitters, so BABIPs could suffer.

That means a hitter who posted a .300/.400/.450 line with 15 home runs in the PCL could quickly turn into a .250/.310/.350 hitter with eight home runs at the MLB level, even if his profile initially seemed safe. Because all non-power categories need to be maximized to compensate for the lack of power, even small deficiencies in contact, walks, power, or BABIP can add up quickly.

The same logic applies to other extreme profiles. For example, a high-strikeout hitter must excel in power, walks, or ideally both. A more balanced profile will always be safer than one missing key components.

Just for fun, I also created a machine learning model trained on K%, ISO, and IFFB% to predict BA and wRC+. The results were not particularly strong, but they did point in an interesting direction.

Figure 8: ML model trying to predict wRC+ and BA from ISO, K% and IFFB%

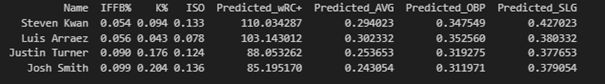

Figure 9: Successful 2024 sub 109 maxEV, sub .150 ISO hitters predicted stats

For example I entered the 4 best performing sub 109/sub.150 ISO hitters of 2024 into the model.The wRC+ values read higher because the run environment was down in 2024 but the BA and SLG values look pretty solid (Figure 9).

On the other hand here are the 4 east successful hitters with those criteria in 2024

Figure 10: unsuccesful hitters

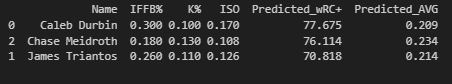

Finally, I entered three well-known hitting prospects projected to be MLB-ready early in 2025. These players fit the soft-hitting, high-contact, high-minor-league-performance criteria. Particularly with Triantos and Durbin, you can see very high pop-up rates. These players are popular late-round fantasy baseball targets in deep or dynasty formats, but the model suggests exercising caution.

Figure 11: soft hitting prospects.

Overall, for these soft-hitting prospects to succeed, they must excel in multiple areas. They must have an elite K rate, some ability to hit for power, and a well-balanced approach—avoiding excessive opposite-field or grounder-focused hitting while prioritizing line drives and hard-hit ground balls. Some flaws may not be exposed in the minors as they will be in the majors, so it’s necessary to go beyond the stat line and dive deep into the underlying metrics.

Of course, machine learning models should be taken with a grain of salt and are not precise projections.

Implications for player development and scouting

For player development and scouting of course this means to train batspeed and get stronger as this will help Exit velocity and in game production. If you can turn a 107 max EV guy into a 110 max EV player that will help his production a lot.

However of course there will also be some players who already need to train very hard to get over 105 and that player might not be able to ever get into the 109 range. If you have such a player there has to be a very sensible approach to development. You do not want a too oppo slappy profile as that will kill even the little power the player has as you at least want to get above .100 ISO or so. That means this player needs to learn to pull some pitches hard into the air. However you also don’t want an extreme pull/flyball approach as this typically tends to supress BABIP which such a Batting average dependent hitter can’t afford. I would say that this hitter needs to selectively pull some pitches early in the count and lay off everything else. For this he needs to learn himself very well and know his hot zones as he can’t really afford to have too many rolled over grounders to the pull side. Later in the count and against good pitchers probably already mid count (1 strike) this hitter probebly should look to have a low line drive gap to gap approach.

Also like with all hitters it helps if he has good pitch selection as chasing increases swing and miss and weak contact.

And finally this hitter must have a great contact rate. He should work on batspeed but still probably have a compact and simple swing as he can’t have volatility but on the other hand the swing can’t get too weak and slappy either.

He definitely needs to avoid pop ups and soft high outfield fly balls. Unless he really has a natural knack for barreling up the high fastball with a flat swing it probably helps if he becomes a good low ball and breaking ball hitter as pitches in the lower third of the zone had a much lower pop up rate (4%) compared to pitches in the upper third of the zone (12%) last season.

Mechanically it can help to have a steeper Vertical bat angle (VBA). VBA is the angle of the bat to the ground at contact. This is achieved by creating side bend in the upper body, the actual bat path should be level to the shoulders but the side bent is tilting the tip of the bat down.

https://x.com/dominikkeul/status/1854614599020015685

This is especially helpful on low pitches where it prevents rolling over to the pull side and allows for hitting the ball straighter into the air. Also the steeper VBA usually creates more oppo flares rather than pop ups when you are late and under which helps the BABIP. The downside is that the steep VBA doesn’t always work as well against high pitches because here a more level bat can help so the steeper VBA works best in conjunction with a low ball approach.

An alternative could also be to work on having a variable level of side bend.

With my hitters for example I’m working on turning through different amounts of side bend with drills like this

https://www.youtube.com/shorts/B9mvq7UkQ34

and also work on level bat high pitch and forced side bend/VBA drills like those

https://www.youtube.com/shorts/-g34eUx7KZo

https://www.youtube.com/shorts/tafKfeG7E18

Not every hitter of course is able to adjust that much, especially against elite pitching velocity which makes it much harder and in that cases it might make sense to focus more on your strengths and match your approach with your strengths.

A general rule is the higher your zone contact rate is the more selective you can be inside the zone and the more you can wait for your pitch while with a little less elite contact ability you should try to of course limit your chase but also increase your zone coverage so that you have less called strikes.